Synthetic Biosensor for Salmonella Detection

Developed a novel biosensor to detect waterborne Salmonella enterica using a SynNotch receptor system.

Summary

This project focused on the design, construction, and preliminary validation of a mammalian-cell–based biosensor capable of detecting Salmonella O-antigens using a SynNotch receptor system. HEK293 cells were engineered to express a surface SynNotch receptor containing an anti-O-antigen scFv and a Myc epitope tag, coupled to a downstream fluorescent reporter (mCherry). Through iterative plasmid preparation, transfection optimization, flow cytometry–based surface expression assays, and co-culture experiments with inactivated model Salmonella/E. coli, our team established proof-of-concept that receptor expression scales with plasmid dose and that reporter activation trends higher in the presence of bacterial antigen.

Motivation and Objectives

Foodborne illness caused by Salmonella enterica remains a significant public health concern. Existing detection methods can be slow, equipment-intensive, or require specialized microbiological expertise. The objective of this project was to develop a modular, cell-based biosensor that translates the presence of Salmonella O-antigens into a fluorescent readout using synthetic biology principles.

Specific objectives included:

- Designing and preparing a SynNotch receptor plasmid targeting Salmonella O-antigens

- Validating surface expression of the receptor in mammalian cells using Myc-tag staining

- Optimizing receptor and reporter plasmid transfection ratios

- Developing a safe bacterial inactivation protocol suitable for mammalian co-culture

- Testing whether the biosensor produces increased reporter output in the presence of model Salmonella antigens

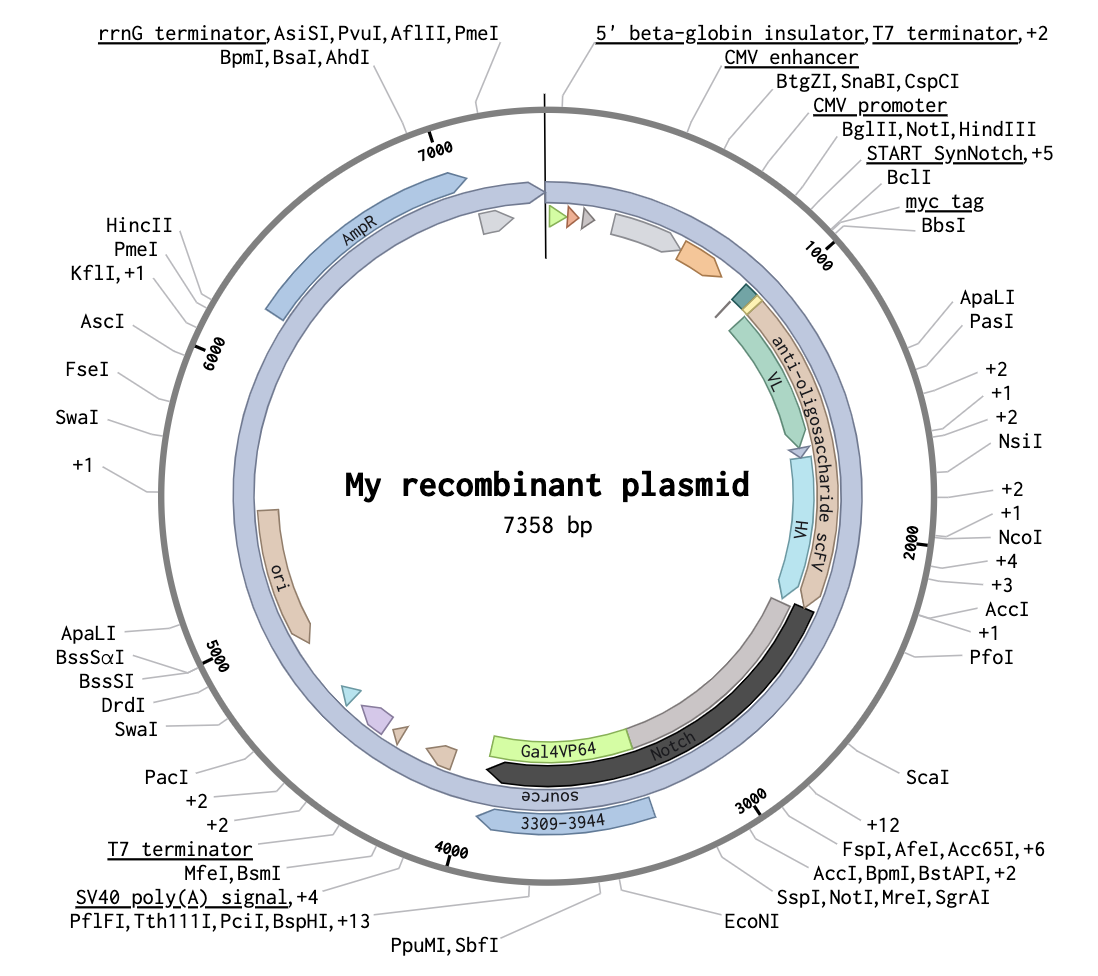

System Design Overview

The engineered system consists of:

- Chassis: HEK293 mammalian cells

- Sensor: SynNotch receptor with an extracellular anti-Salmonella O-antigen scFv and an extracellular Myc tag (for surface detection)

- Signal transduction: ligand-induced SynNotch cleavage releasing an intracellular transcriptional activator (Gal4-VP16)

- Output: Gal4-driven transcription of a fluorescent reporter (mCherry) for quantitative single-cell readout

This design decouples antigen recognition from reporter expression and keeps the system modular (receptors and outputs can be swapped in future iterations).

Experimental Workflow (High-Level)

Plasmid preparation and handling

Plasmids were resuspended, transformed into E. coli, streaked for single colonies, expanded in selective media, and archived as glycerol stocks. Plasmids were isolated via miniprep and quantified using Nanodrop, with multiple colonies processed for redundancy.

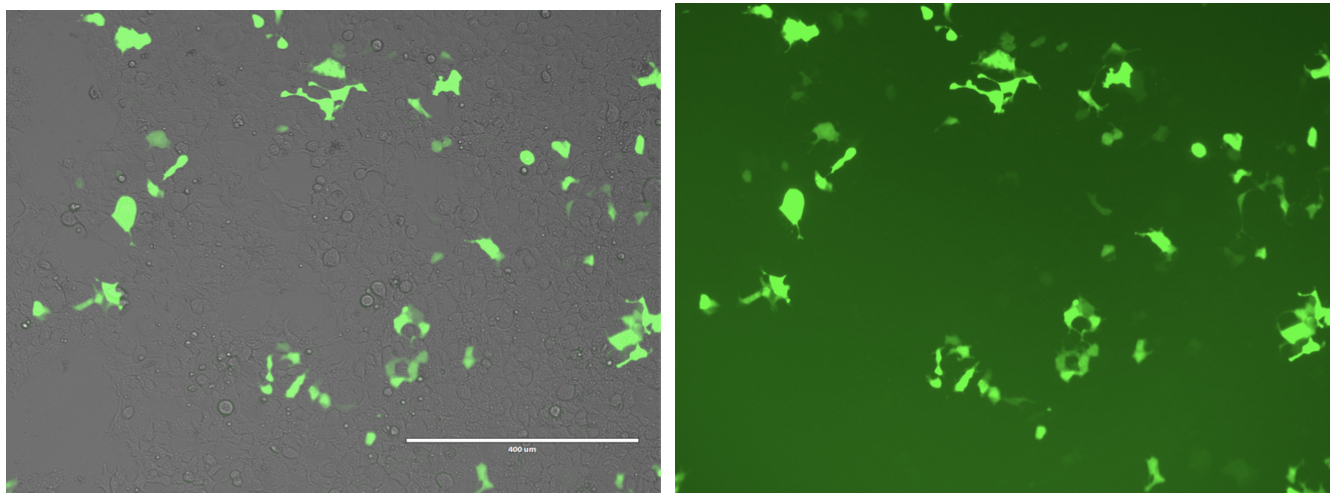

Transfection verification (Comet GFP)

To verify that our transfection workflow was functioning, we intentionally transfected a Comet GFP plasmid. Cells fluoresced following transfection, confirming successful delivery and expression of the Comet GFP construct.

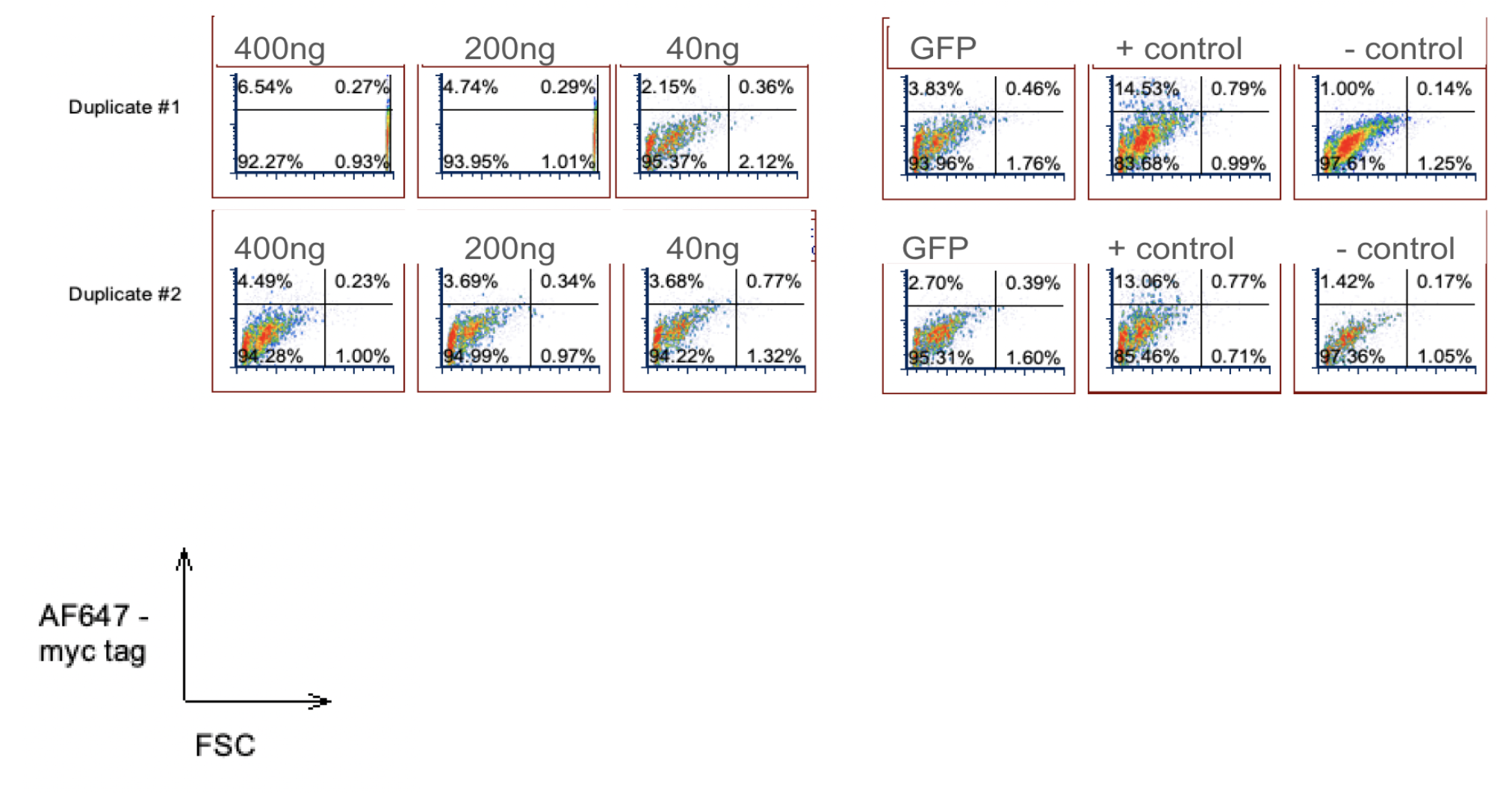

Myc-tag staining and flow cytometry (surface expression)

Two rounds of Myc-tag surface staining were performed to assess SynNotch receptor surface expression as a function of receptor plasmid dose:

- First Myc stain: Dose-dependent increases in Myc signal (40 ng → 400 ng), confirming surface expression but with low positive-cell fractions.

- Second Myc stain: Protocol optimizations (longer expression time, gentler harvesting, revised plasmid concentrations) improved data quality; 1500 ng receptor plasmid produced ~3× higher Myc-tag signal than 500 ng.

Flow cytometry was chosen for quantitative, single-cell–resolution assessment of heterogeneous expression across cell populations.

Reporter expression and leakiness analysis

Reporter-only and receptor+reporter conditions were compared to evaluate baseline leakiness. Positive controls using constitutive Gal4-VP16 showed strong mCherry expression, while negative controls showed minimal signal. Lower reporter plasmid doses reduced leakiness, and a 1:1 receptor-to-reporter ratio was selected as a practical compromise for downstream sensing experiments.

Model bacteria culture, inactivation, and co-culture

A model Salmonella/E. coli strain was cultured and tested under multiple inactivation strategies (heat, cold, ethanol). After iterative evaluation of bacterial survival and mammalian cell safety, heat inactivation was selected for co-culture experiments. Optical density measurements were used to estimate bacterial concentration and choose bacteria-to-mammalian-cell ratios; a high excess of bacteria was used to maximize the likelihood of SynNotch activation.

HEK293 cells transfected with receptor and reporter plasmids were co-cultured with heat-inactivated model bacteria (triplicate wells with bacteria, triplicate wells without bacteria, plus positive/negative controls), then analyzed by fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry.

Results (Summary)

- Receptor expression: Myc-tag flow cytometry confirmed that receptor surface expression increases with receptor plasmid dose; protocol refinements significantly improved signal quality.

- Cell viability and morphology: Microscopy showed no major morphological differences between cells cultured with or without inactivated bacteria, indicating the bacterial treatment was effective and non-toxic under the tested conditions.

- Reporter activation: Positive controls exhibited strong reporter expression. Experimental groups showed modest but consistent trends, with higher reporter output in bacteria-exposed wells relative to matched no-bacteria controls across multiple replicates.

Challenges and Limitations

- Sourcing genetic parts: scFv sequences and SynNotch backbones were difficult to locate due to intellectual property constraints.

- Expression efficiency: Early experiments produced low receptor-positive fractions, requiring protocol iteration and optimization.

- Bacterial inactivation: Multiple iterations were required to ensure safety without compromising antigen integrity.

Future Work

- Increase replicate count and refine controls for co-culture experiments

- Systematically vary receptor-to-reporter ratios and bacterial concentrations

- Test isolated O-antigens instead of whole bacteria to improve specificity and safety

- Evaluate higher-affinity / better-characterized anti-Salmonella scFvs

- Add dynamic measurements (e.g., time-lapse imaging) to study activation kinetics

Recombinant Plasmid Map

Appendix

- Plasmid sequence (PDF): My recombinant plasmid sequence

- Video presentation: Project presentation (YouTube)

References

- “Estimating the Burden of Foodborne Diseases.” World Health Organization, World Health Organization, www.who.int/activities/estimating-the-burden-of-foodborne-diseases. Accessed 27 Oct. 2023.

- “NCEZID: Foodborne Disease (Food Poisoning).” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 17 Dec. 2019, www.cdc.gov/ncezid/what-we-do/our-topics/foodborne-disease.html. Accessed 27 Oct. 2023.

- “New Report Highlights Disparate Impact of Foodborne Illness on Poor and Minority Communities.” Consumer Federation of America, 19 Jan. 2021, consumerfed.org/press_release/new-report-highlights-disparate-impact-of-foodborne-illness-on-poor-and-minority-communities/. Accessed 27 Oct. 2023.

- Carothers, Meredith. “Clean Then Sanitize: A One-Two Punch to Stop Foodborne Illness in the Kitchen.” USDA, 27 Aug. 2019, www.usda.gov/media/blog/2019/08/27/clean-then-sanitize-one-two-punch-stop-foodborne-illness-kitchen. Accessed 27 Oct. 2023.

- Shen, Y, Xu, L, Li, Y. “Biosensors for rapid detection of Salmonella in food: A review.” Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2021;20:149–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12662

- “Salmonella and Food.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 5 June 2023, www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/communication/salmonella-food.html. Accessed 27 Oct. 2023.

- “Bacterial Serotyping Guide for Salmonella.” Bio-Rad, www.bio-rad.com/webroot/web/pdf/fsd/literature/FSD_14-0699.pdf. Accessed 27 Oct. 2023.

- RCSB Protein Data. “1MFC: High Resolution Structures of Antibody Fab Fragment Complexed with Cell-Surface Oligosaccharide of Pathogenic Salmonella.” RCSB PDB, www.rcsb.org/structure/1mfc. Accessed 27 Oct. 2023.

- “Escherichia coli (Migula) Castellani and Chalmers - 25922.” ATCC, www.atcc.org/products/25922. Accessed 27 Oct. 2023.

- Hu, Mengyi, and Joshua B. Gurtler. “Selection of Surrogate Bacteria for Use in Food Safety Challenge Studies: A Review.” Journal of Food Protection, Volume 80, Issue 9, 2017.

- “Gal4-VP16 (Plasmid #71728).” Addgene, www.addgene.org/71728/. Accessed 27 Oct. 2023.

- Ahmad, Zuhaida Asra, et al. “ScFv Antibody: Principles and Clinical Application.” Clinical & Developmental Immunology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2012, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3312285/. Accessed 27 Oct. 2023.

- Sagripanti JL, Hülseweh B, Grote G, Voss L, Böhling K, Marschall HJ. “Microbial inactivation for safe and rapid diagnostics of infectious samples.” Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011 Oct;77(20):7289–7295. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.05553-11

- Espinosa, Maria Fernanda, A. Natanael Sancho, Lorelay M. Mendoza, César Rossas Mota, and Matthew E. Verbyla. “Systematic review and meta-analysis of time-temperature pathogen inactivation.” International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, Volume 230, 2020.

- Trivedi, Vikas D., Karishma Mohan, Todd C. Chappell, Zachary J. S. Mays, and Nikhil U. Nair. “Cheating the Cheater: Suppressing False-Positive Enrichment during Biosensor-Guided Biocatalyst Engineering.” ACS Synthetic Biology 2022;11(1):420–429. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssynbio.1c00506

- Sin ML, Mach KE, Wong PK, Liao JC. “Advances and challenges in biosensor-based diagnosis of infectious diseases.” Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2014 Mar;14(2):225–244. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737159.2014.888313

- Lorenzo-Díaz F, Fernández-López C, Lurz R, Bravo A, Espinosa M. “Crosstalk between vertical and horizontal gene transfer: plasmid replication control by a conjugative relaxase.” Nucleic Acids Res. 2017 Jul 27;45(13):7774–7785. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx450

- Yung, Mimi. “Comparison of Kill Switch Toxins in Plant-Beneficial …” ACS Synthetic Biology, 2022, https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acssynbio.2c00386

- Xu, Meng, et al. “An Electrochemical Biosensor for Rapid Detection of E. coli O157:H7 with Highly Efficient Bi-Functional Glucose Oxidase-Polydopamine Nanocomposites and Prussian Blue Modified Screen-Printed Interdigitated Electrodes.” Analyst, The Royal Society of Chemistry, 15 June 2016, https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2016/an/c6an00873a

- Cygler, Miroslaw, Shan Wu, Alexander Zdanov, David R. Bundle, and David R. Rose. “Recognition of a carbohydrate antigenic determinant of Salmonella by an antibody.” Biochem Soc Trans. 1 May 1993;21(2):437–441. https://doi.org/10.1042/bst0210437

- Lorenzo-Díaz F, Fernández-López C, Lurz R, Bravo A, Espinosa M. “Crosstalk between vertical and horizontal gene transfer: plasmid replication control by a conjugative relaxase.” Nucleic Acids Res. 2017 Jul 27;45(13):7774–7785. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx450

- Hu, Mengyi, and Joshua B. Gurtler. “Selection of Surrogate Bacteria for Use in Food Safety Challenge Studies: A Review.” Journal of Food Protection, Volume 80, Issue 9, 2017.

- Shen, Y, Xu, L, Li, Y. “Biosensors for rapid detection of Salmonella in food: A review.” Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2021;20:149–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12662

- Espinosa, Maria Fernanda, A. Natanael Sancho, Lorelay M. Mendoza, César Rossas Mota, and Matthew E. Verbyla. “Systematic review and meta-analysis of time-temperature pathogen inactivation.” International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, Volume 230, 2020.